Wiping an eMMC

Wiping hard drives is a weird topic. It seems like a pretty fundamental thing to do, but the actual procedure to follow seems to be shrouded in mystery. If you ask 50 people how to wipe a hard drive, you'll probably get 50 similar yet distinct answers. Do you fill the disk with ones, zeroes, or random garbage? Does it matter? Do you only need to do that once, or does it take a few passes? I've never been satisfied with all the uncertainty around these details, so I set off to figure out what it actually takes.

I know that not all memory is created equal. I'm almost certain that different memory technologies will have slightly different procedures, so to get a detailed answer, we'll need to focus on a specific type of memory. For this investigation, I'll dive into a specific type of memory I've used quite a bit — the humble eMMC. These have become the de facto choice for memory in "beefy" embedded systems (e.g. powerful enough to run Linux), so knowing how to securely erase data from them seems pretty useful.

What is an eMMC, anyway?

Before diving too deep into eMMCs, it will help to have some context about flash memory in general. There are two rough categories of flash memory: raw and managed.

Raw flash memory is pretty straightforward. These are your run of the mill NAND/NOR/SPI flash chips, and they're pretty ubiquitous in embedded systems. I personally think of them as "dumb" flash devices. If you read, write or erase data from a certain location in raw flash memory, the flash chip simply obeys your command. So as a programmer, you can just treat raw flash memory as a big (and very slow) array, right? Well, you can, but you'll run into issues pretty quickly.

To start with, once you set a bit in flash memory by writing to it, you can't "write" it back to a cleared state. You need to erase it first. That doesn't sound so bad, except there are a few wrinkles:

-

Erasing is often orders of magnitude slower than writing

-

Erases can only be performed on relatively large blocks of memory. These erase blocks are normally measured in kilobytes, and generally, they grow with the size of the flash memory.

-

Erase blocks normally wear out independently from each other, so if you continuously write and erase the same sections of flash over and over again, those sections will die before the rest of the device. Most usage patterns for non-volatile memory don't uniformly distribute writes across all the available space, so this is a very real concern. Mitigating this is referred to as wear leveling.

You need to keep all of this in mind when writing software that directly interacts with raw flash memory. Thankfully, if you're in Linux, you can avoid most of this by simply using a filesystem like UBIFS, which is designed to be used with raw flash memory. But at the end of the day, your CPU is executing the instructions that manage the performance and wear of the flash device.

So, uh, eMMCs?

Right. eMMCs are managed flash devices. The general idea behind managed flash is very simple — in terms of physical storage, these devices are made of the same stuff as raw flash memory, but all the complexity of managing erases and wear leveling is offloaded to the device itself. You can think of managed flash devices as having their own little microcontrollers embedded inside them, implementing the exact same algorithms as something like UBIFS.

How do those algorithms actually work in an eMMC? It's pretty simple at a high level.

-

Externally, the eMMC expose a contiguous, addressable range of memory to users (i.e. you and your kernel). The size of this memory matches the advertised size of the device. If you have a 4GB eMMC, you can write anywhere from

0x00000000to0xffffffff. You can think of this as the public API of the eMMC — users can read and write to any location within this address space. -

Internally, the eMMC includes more flash memory than is actually advertised. This varies by device, and it's more or less impossible to tell how much "real" storage an eMMC has without asking the manufacturer. But there's always some extra memory available.

-

The eMMC maintains a map between its public address space and the address space of the device's underlying physical memory. If you replace "public" with "virtual", this is very similar to how virtual memory works. With virtual memory, processes (the end-users of the memory) have no idea how a specific virtual address maps to the underlying physical memory. Similarly, with an eMMC, the filesystem and block driver (the end-users of the memory) have no idea how a specific offset from the start of the eMMC maps to its underlying flash memory.

The eMMC standard (more on that later) provides some terminology to help with this.

-

The sections of flash memory that are currently mapped to an address and can be accessed externally make up the Mapped Host Address Space.

-

The rest of the flash memory, which is not externally accessible, makes up the Unmapped Host Address Space.

-

Just to be thorough, I should also mention that there's the Private Vendor Specific Address Space. This doesn't store any user data, but instead stores the data required by the device for its own internal management. As an example, this might store the address mapping table itself, as well as erase counters and other metadata needed to implement wear leveling. This isn't directly available externally, although vendors often provide this information through dedicated commands for diagnostic purposes. I'll be ignoring this section since it doesn't store any of the data we want to erase. If you want to erase all the data and metadata from an eMMC, you'll have to figure that out on your own.

To help solidify this, let's run through a few examples of how an eMMC actually implements writes and erases. For these examples, we'll use a hypothetical eMMC with a few made up (and silly) characteristics:

-

3 bit address space (i.e. 8 blocks of publicly accessible memory)

-

12 blocks of underlying flash memory

-

Writes have a minimum length of 1 block and can be addressed to any block

-

Erases have a minimum length of 2 blocks and must be aligned to 2 blocks

To start with, we can assume that the public address space maps directly to the underlying physical memory, and the first 8 physical blocks correspond to the first 8 addresses provided to users.

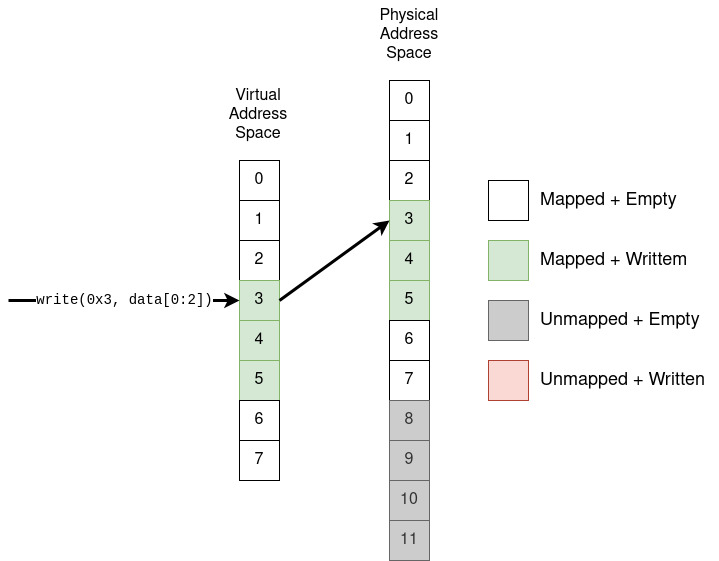

What happens when you try to write 3 blocks of data an arbitrary address?

The first write is pretty straightforward. None of the blocks have been written to, so the eMMC can just write to the mapped blocks without any sleight of hand. Remember, writes to flash memory are very cheap compared to erases.

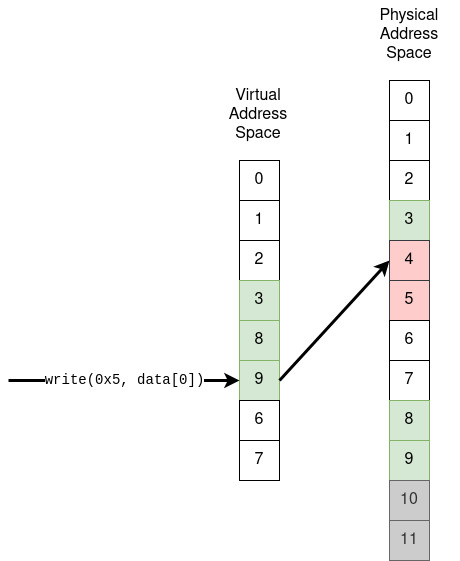

What happens if you then try to overwrite the block at address 5? Things are a little more complicated.

-

Since the eMMC uses raw flash memory under the hood, it can't simply "overwrite" bits that have already been set. It needs to perform an erase first.

-

Even though writes are addressable to individual blocks, if that block requires an erase, the eMMC needs to consider the minimum erase size and alignment requirements of the underlying memory.

To handle this request as quickly as possible, the eMMC does the following:

-

Remaps the two erase-aligned physical blocks,

4and5to two unmapped but empty blocks,8and9. -

Writes the previous value from physical block

4into physical block8, since this write is not modifying this block. -

Writes the new value from the request into physical block

9.

Updating the mapping table is cheap, and so is writing to the previously unmapped but empty blocks. So as a whole, these

steps are much faster than erasing blocks 4 and 5, waiting for that to complete and then writing the new data into

the freshly erased blocks.

So what happens to those previously mapped blocks that still have data in them? Well, that's where things get a little hand-wavey. This is essentially an implementation detail of the eMMC. For the most part, we can assume that the microcontroller in the eMMC is running its own scheduler of sorts, trying to sneak in "asynchronous" erases when it isn't processing requests. The actual algorithms are likely more complicated, but in general, the eMMC tries to "hide" the erases from you if it can, since any erase results in slow, blocking I/O.

Now, this post isn't about how to implement your own managed flash device. I've never worked on that myself, and I'm sure that my simplified model presented here glosses over a lot of the details involved. This post is about wiping an eMMC, not designing an eMMC. There's one key takeaway from these examples — after writing or erasing data from an eMMC, there's a reasonable chance that previously written data is still present in unmapped sections of physical memory.

Now, depending on your requirements, this might not matter. If you consider the eMMC "wiped" once there's no data available in the mapped address space, you can probably disregard the unmapped sections of memory entirely. However, if the data being stored is very sensitive, you may need to deal with this. This is a concern in my case, so the journey isn't over yet.

Welcome, JESD84!

JESD84 is the standard describing both the hardware and software interface of eMMC devices. The most recent version of the eMMC standard is 5.1, and it's freely available from the JEDEC website

Skimming through the standard, a few commands available in the eMMC communication protocol seem promising:

- Secure Erase

- Secure TRIM

- Sanitize

The standard provides a pretty strong disclaimer about the first two options:

NOTE Secure Erase/TRIM is included for backwards compatibility. New system level implementations (based on v4.51 devices and beyond) should use Erase combined with Sanitize instead of secure erase.

All right then. It sounds like Erase and Sanitize are the things to check out. In fact, Sanitize sounds like exactly what we're looking for.

The use of the Sanitize operation requires the device to physically remove data from the unmapped user address space [...]

[...] After the sanitize operation is completed, no data should exist in the unmapped host address space.

So based on that description, it seems like we have a good recipe for wiping an eMMMC.

- Ensure that all data has been removed from the mapped address space.

- Trigger the Sanitize operation, wiping any data left over in the unmapped address space.

There's one catch with this. It turns out there are actually three separate commands you can use to erase data from the mapped address space.

- Erase

- TRIM

- Discard

Here's a quick blurb from the standard about each of them.

Erase: Erase the erase groups identified by CMD35&36. Controller can perform actual erase at a convenient time. (legacy implementation)

TRIM: Erase (aka Trim) the write blocks identified by CMD35&36. The controller can perform the actual erase at a convenient time.

Discard: Discard the write blocks identified by CMD35 & 36. The controller can perform partial or full the actual erase at a convenient time.

From that, we can conclude a few things:

-

TRIM and Discard generally seem better than Erase. They can be addressed to individual write blocks rather than (larger) erase blocks, and Erase seems to be included for backwards compatibility.

-

The differences between TRIM and Discard are not entirely clear. Discard may do a "partial" erase?

Thankfully, the Discard section provides a very relevant disclaimer:

When Sanitize is executed, only the portion of data that was unmapped by a Discard command shall be removed by the Sanitize command. The device cannot guarantee that discarded data is completely removed from the device when Sanitize is applied.

Yikes. So in order to wipe our eMMC, we want to be really, really sure that we aren't "discarding" the data. This requires a small tweak to our original plan.

- Erase all data from the mapped address space using Erase or TRIM.

- Trigger the Sanitize operation, wiping any data left over in the unmapped address space.

Now that we have a plan, we should figure out how to actually do this.

The eMMC in Linux

The Linux kernel provides a single driver subsystem, mmc, which provides a block device interface for a variety of MMC devices (e.g. eMMCs,

SD cards). To figure out how to implement our design, we need to figure out how that driver implements erases and sanitization for eMMC devices.

Sanitization

Thankfully, sanitization is pretty simple. Taking a peek through the mmc code, it seems like the block device supports the dedicated sanitization

command through an ioctl(2) interface. This can be confirmed by checking the helpful mmc-utils source code.

int do_sanitize(int nargs, char **argv)

{

// setup [...]

ret = write_extcsd_value(fd, EXT_CSD_SANITIZE_START, 1);

// cleanup [...]

}int write_extcsd_value(int fd, __u8 index, __u8 value)

{

// setup [...]

ret = ioctl(fd, MMC_IOC_CMD, &idata);

// cleanup [...]

}That's pretty straightforward. If we want to sanitize the eMMC after erasing data from it,

we can either call ioctl(2) from our own code, or just use mmc-utils from the command line.

Erasing

The erasing situation is more complicated. Unlike sanitization, erases aren't normally triggered by userland applications. There are two normal ways to erase things from a block device.

-

If the device hosts a filesystem, you can delete files from the filesystem.

-

If the memory doesn't host a filesystem, or if you don't care about the integrity of the filesystem, you can write data to the underlying block device.

Since we're trying to wipe everything, option 2 is the better option for us. So what we really want to understand is how the eMMC device driver handles writes and erases directly to the block device.

When a userland program or filesystem tries to modify a block device, this is the rough sequence of events:

-

The requested change is passed to the driver corresponding to the block device. For an eMMC, this is the

mmcmodule. -

The request is submitted to a request queue provided by the block device. Like most device drivers, block device drivers provide an instance of a structure (

struct blk_mq_ops), binding "generic" function pointers for this type of device driver to device-specific callbacks.

Here's the specific callbacks provided by the mmc driver.

static const struct blk_mq_ops mmc_mq_ops = {

.queue_rq = mmc_mq_queue_rq,

.init_request = mmc_mq_init_request,

.exit_request = mmc_mq_exit_request,

.complete = mmc_blk_mq_complete,

.timeout = mmc_mq_timed_out,

};The mmc subsystem binds the queue_rq callback to mmc_mq_queue_rq. That function does a few sanity checks

(e.g. are there a bunch of queued requests that are still waiting to be processed?), but assuming that goes well,

the request is dispatched to mmc_blk_mq_issue_rq, which processes the request.

The Linux kernel provides a pretty wide range of generic requests that can be sent to block devices. The full list of

request types are defined in blk_types.h. As far as erasing goes, a few request types seem relevant.

REQ_OP_WRITEREQ_OP_DISCARDREQ_OP_SECURE_ERASEREQ_OP_WRITE_ZEROES

To start with, REQ_OP_WRITE_ZEROES isn't supported by mmc_blk_mq_issue_rq, so we can ignore that.

REQ_OP_SECURE_ERASE seems helpful, but searching through the kernel, this request only seems to be triggered through certain

filesystem operations. As far as I can tell, if we wipe an entire device with dd, this request will never be used.

That leaves us with two operations. REQ_OP_WRITE is pretty straightforward. When the mmc driver gets this request, it sends

the device a block write request without any dedicated Erase, TRIM or Discard. Since the eMMC standard doesn't mention anything

about automatic erases performed by writes not working with Sanitize, we can assume that this will "just work".

REQ_OP_DISCARD is not as simple. When this request is received, the mmc driver calls mmc_blk_issue_discard_rq. Once that

function does some sanity checks, it calls this function to actually perform the erase:

err = mmc_erase(card, from, nr, card->erase_arg);What is card->erase_arg? It turns out that's set in mmc_init_card.

if (mmc_can_discard(card))

card->erase_arg = MMC_DISCARD_ARG;

else if (mmc_can_trim(card))

card->erase_arg = MMC_TRIM_ARG;

else

card->erase_arg = MMC_ERASE_ARG;Well, there we have it. It looks like the mmc driver prefers Discard over TRIM and TRIM over Erase.

So if our eMMC supports the Discard command, there's a pretty good chance that most of the data we

"erased" was actually "discarded", which means that the Sanitize command may not actually erase it

from the unmapped blocks in the eMMC.

Where does this all leave us?

With all of this under our belt, it's pretty clear that you might run into issues securely wiping

data from an eMMC using the mainline Linux kernel. One simple workaround would simply be commenting out

the mmc_can_discard check from the mmc driver, forcing the driver to only use TRIM or Erase commands.

Alternatively, you could try and add some configuration switch into the mmc subsystem to disable the

Discard command dynamically. There are a few ways to go about this:

-

Add a switch to the Kconfig for the

mmcdriver. You'd have to decide when building the kernel whether or not you care about the potential performance tradeoff. -

Add a property to the device tree node for eMMC devices specifying the behaviour. This would let the same kernel support either configuration, but the decision would still need to be made at build time.

-

Add an argument to the kernel command-line, which is parsed by the

mmcdriver during its probe.

All of that goes beyond the scope of this post. I was mainly just curious what it actually takes to properly wipe an eMMC used in an embedded Linux system. As it turns out, the answer is pretty complicated.